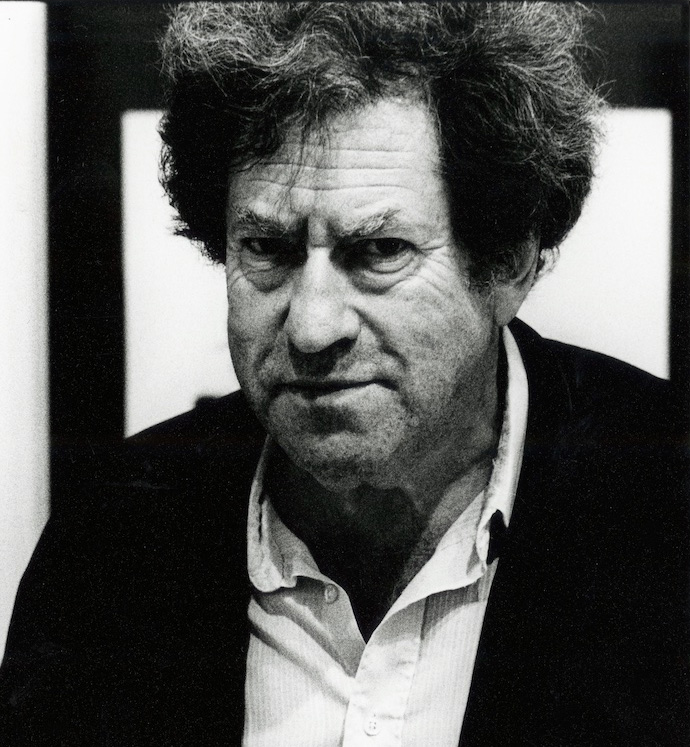

The artist

Biography

Felix Rozen was a French painter whose multifaceted work was marked by the traumas and innovations of the 20th century.

Rozen first lived the exile, the mourning, the chaos of the world before inventing his own language that allowed him, whether in painting, sculpture or music, to devise works that also tell the beauty of things.

“When childhood is in ruins and history relentlessly deconstructs people, how many men could say, like Max Jacob, that in terms of suffering they have ‘plenty of memory’? Felix Rozen is one of them,” writes essayist Nicole Ambourg.

Born in Moscow on January 12, 1938, to Austro-Polish music lovers, Felix Rozenman, called Felix Rozen, came into the world in the worst period of contemporary European history. His father, an internationalist activist, evacuated him south of the Urals in 1941, with his sister and mother, whose family was exterminated in the Nazi camps. Felix’s older brother died on the Belarusian front in 1944. After the war, the family followed the father’s missions as cultural attaché at the Polish Embassy in Prague before moving to Warsaw in 1948. In 1952, they spent a year in Helsinki. On January 1, 1956, when he was just 17, Felix Rozen’s mother died of cancer. Already drawn to painting, he nevertheless decided to study at the Electronics School of Warsaw before being admitted to the Academy of Fine Arts in 1959, where he received a very complete training in engraving, drawing, photography, interior architecture and furniture design.

A year after his father’s death, and anticipating the drift of political events in Poland, he went into exile in Paris in 1966, at the age of 28, accompanied by his first wife, Elżbieta Koślacz, an actor. “Art was in France, all the artists lived in Paris,” he would say later. Paris, a city he already knew. He had made short stays there, befriending Sonia Delaunay, Zadkine and the mime Marcel Marceau (read the story of these early years in Rozen by Rozen).

He settled in the Montparnasse neighborhood at the home of Xana Pougny, the widow of the Franco-Russian painter Jean Pougny. There, the painter Kikoïne advised him to shorten his name to Rozen.

In 1967, he spent several months in residence at the Royaumont Abbey, alongside, among others, photographer Gisèle Freund, who remained a faithful friend and whose portraits he admired, realizing that “everything is seen on a face.” His figurative and representational paintings were still influenced by the School of Paris, in particular Soutine. He painted with oils and seriously applied himself to engraving.

In 1970, his first daughter was born. He then divided his time between Paris and Collias, a village in the Gard where the baker was none other than his cousin, Ernest Frankel, a former resistance fighter and survivor of Dachau and Buchenwald. There, Rozen spent years renovating a small house where he would work every summer, enjoying, like Chagall, Cézanne or his contemporary Anselm Kiefer, the light radiating from the garrigue and filling their studios. He made a definitive break with realism. In 1972 and 1973, he created and directed the Collias Festival, inviting famous musicians, painters and filmmakers. Jean-Louis Trintignant, a neighbor, lent them his courtyard for a theatrical creation.

In 1974, Felix Rozen became a French citizen; and exhibited at the Simone Badinier Gallery canvases that were “bursting with brilliance, [expressing] a wild commitment of spirit and heart,” the poet Pierre Béarn wrote.

That same Spring, he met art critic Georgina Oliver, who became his second wife and with whom he had four children.

Over the decades, he branched out into a multiplicity of artistic fields, becoming a sculptor, author and actor of performances, poster artist for French public radio France Culture and director of short films. He also taught at the École des Beaux-Arts in Besançon, the University of Vincennes and the Sorbonne.

From 1977 onward Felix Rozen lived and worked in Boulogne-Billancourt where he obtained, thanks to the support of the painter Georges Mathieu, a work space near Île Seguin.

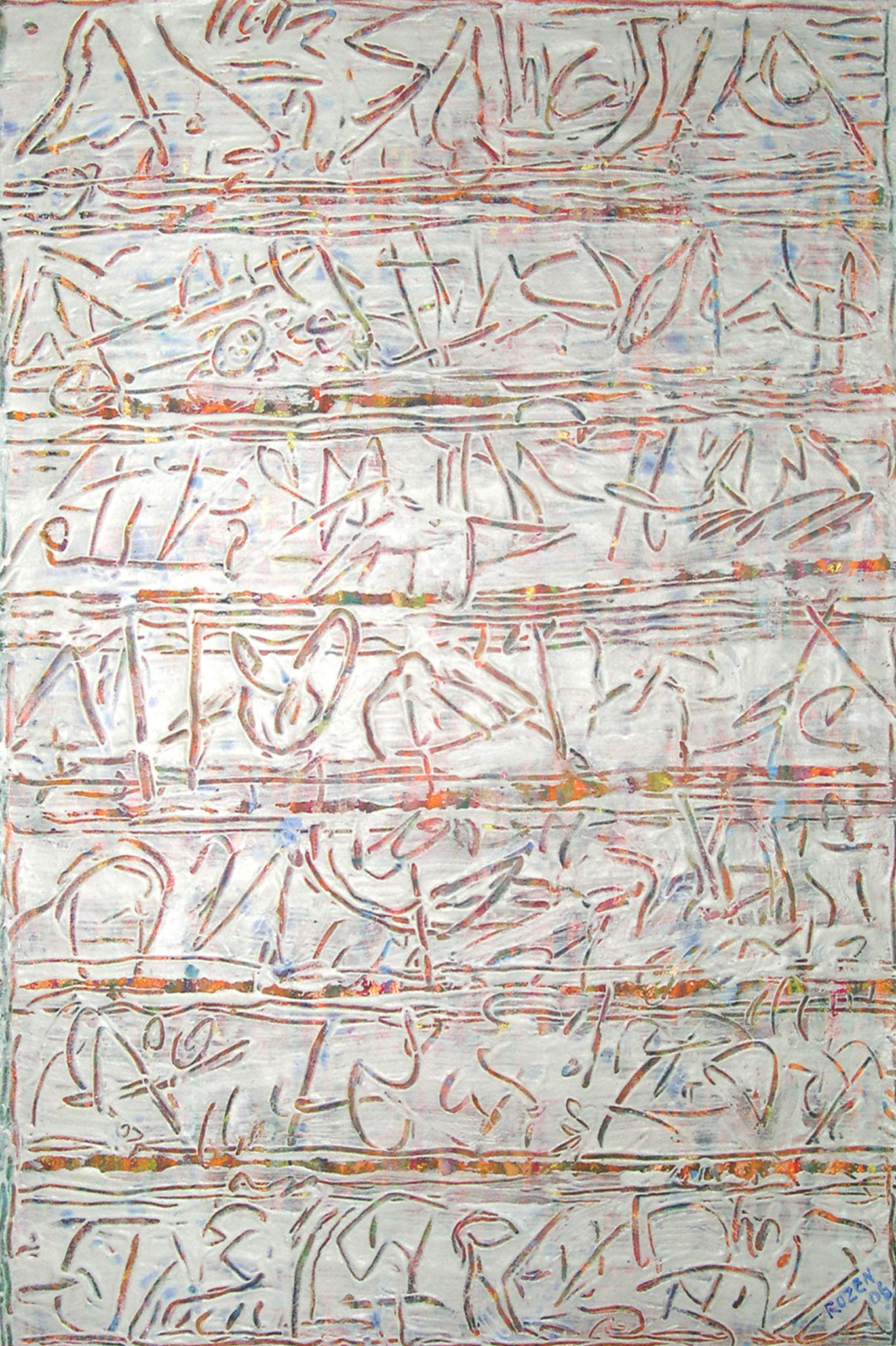

Felix Rozen next sought to elaborate a compositional language of his own. He who had always dreamed of becoming a conductor compiled notebooks bearing witness to abundant research around symbols and abstract signs, mixing music and painting. His works evolved, suggesting archaeological strata. The poet and essayist, Jacques Lacarrière, a promirent Hellenist, spoke of “palimpsests”.

At this moment, he got closer to Christian Dotremont and Pierre Alechinsky, members of the COBRA movement, and began a series of photographic portraits of artists.

In 1977, he participated in group exhibitions with Bram Van Velde, Aristide Caillaud, Jean Messagier.

In 1979-1980, he spent several months in New York. At the Chelsea Hotel, he worked on lines and zigzags, wax and pigments (New York Series).

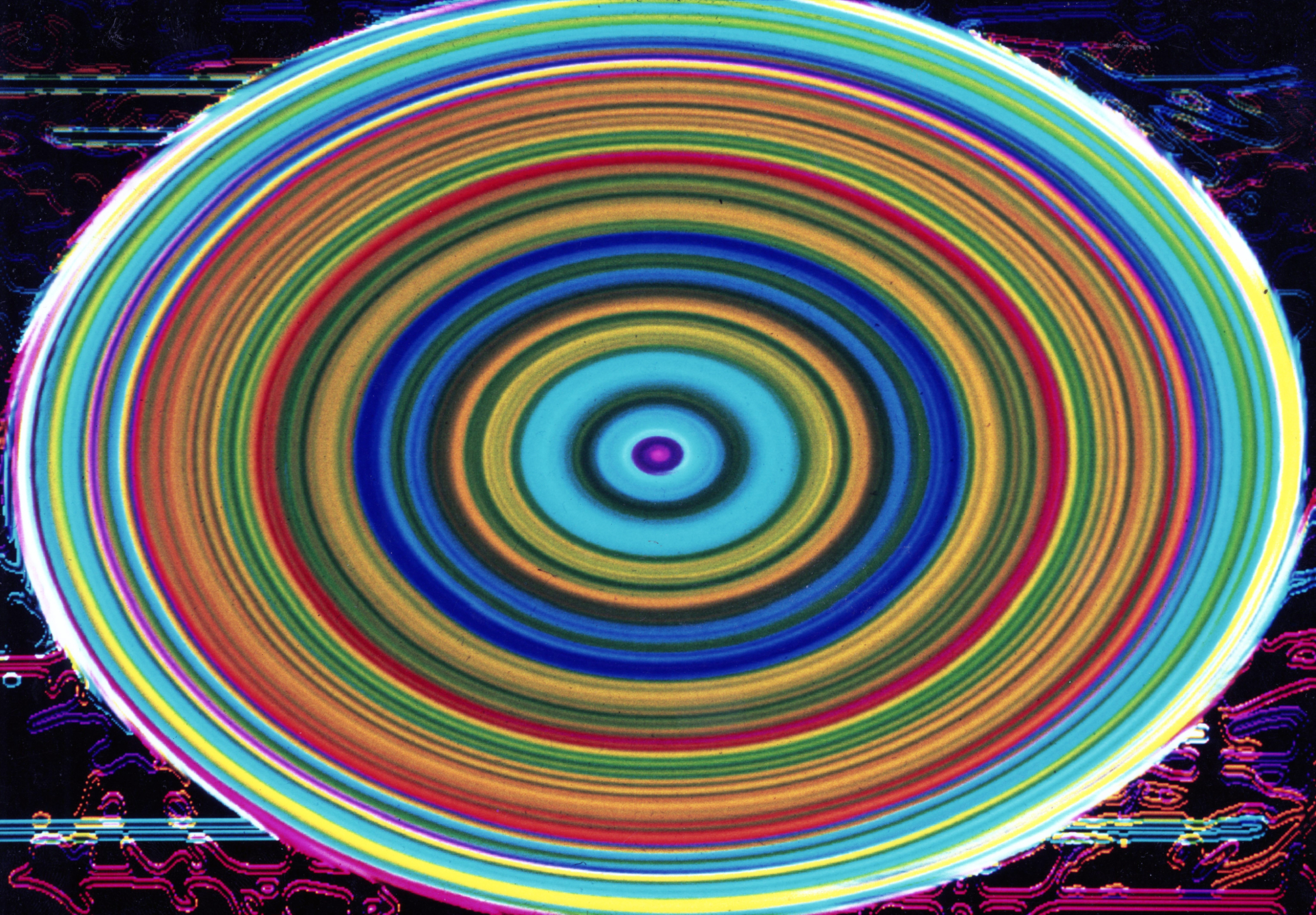

Back in France, music was now at the heart of his experiments in the visual arts. In January 1981, he created for Jean-Yves Bosseur and the Intervalles ensemble the graphic score Uncertain Opus. This would open the doors of the Center for Music Experiment in San Diego and New York University, where his computer-generated Computer Series combined sounds, images and computer science.

In 1985, Felix Rozen went to Tokyo. He worked on Japanese paper, to which he attributed a key quality: that it allows “colors to vibrate.” His Tokyo Series attests to this.

In 1990, he developed a wax and fire engraving process called Pyrocera, which he patented at France’s National Institute of Industrial Property. He extended this process to painting, which enabled him in his series Mysteries and Double Vision, both a type of low-relief-sculpture, as he himself called them, to create a third pictorial dimension, evoking time.In 2004, a retrospective was organized at the Musée des Années 30 in Boulogne-Billancourt. In December 2005, the Jeanne Bucher Gallery dedicated an exhibition to him focusing on his Letters to Paul Klee.

The Plagales Sequences, London Calling, Venice Calling and Digital Traces followed: collecting from his printer scraps of offset reproductions from his catalogs, he transformed them, covering them with layers of paint that he scratched, clawed or caressed with specially-conceived one-of-a-kind tools producing small-format works.

In 2010, though suffering from a neurodegenerative disease, he did not drop his paintbrushes. His sense of perception was modified, blurred… leading to the emergence of a Série floue/Blurry Series, which has never been exhibited. He died on October 6, 2013. His loved ones created an association to share his work with the general public.

Felix Rozen was a French painter whose multifaceted work was marked by the traumas and innovations of the 20th century. Rozen first lived the exile,…

Felix Rozen was a French painter whose multifaceted work was marked by the traumas and innovations of the 20th century.

Rozen first lived the exile, the mourning, the chaos of the world before inventing his own language that allowed him, whether in painting, sculpture or music, to devise works that also tell the beauty of things.

“When childhood is in ruins and history relentlessly deconstructs people, how many men could say, like Max Jacob, that in terms of suffering they have ‘plenty of memory’? Felix Rozen is one of them,” writes essayist Nicole Ambourg.

Born in Moscow on January 12, 1938, to Austro-Polish music lovers, Felix Rozenman, called Felix Rozen, came into the world in the worst period of contemporary European history. His father, an internationalist activist, evacuated him south of the Urals in 1941, with his sister and mother, whose family was exterminated in the Nazi camps. Felix’s older brother died on the Belarusian front in 1944. After the war, the family followed the father’s missions as cultural attaché at the Polish Embassy in Prague before moving to Warsaw in 1948. In 1952, they spent a year in Helsinki. On January 1, 1956, when he was just 17, Felix Rozen’s mother died of cancer. Already drawn to painting, he nevertheless decided to study at the Electronics School of Warsaw before being admitted to the Academy of Fine Arts in 1959, where he received a very complete training in engraving, drawing, photography, interior architecture and furniture design.

A year after his father’s death, and anticipating the drift of political events in Poland, he went into exile in Paris in 1966, at the age of 28, accompanied by his first wife, Elżbieta Koślacz, an actor. “Art was in France, all the artists lived in Paris,” he would say later. Paris, a city he already knew. He had made short stays there, befriending Sonia Delaunay, Zadkine and the mime Marcel Marceau (read the story of these early years in Rozen by Rozen).

He settled in the Montparnasse neighborhood at the home of Xana Pougny, the widow of the Franco-Russian painter Jean Pougny. There, the painter Kikoïne advised him to shorten his name to Rozen.

In 1967, he spent several months in residence at the Royaumont Abbey, alongside, among others, photographer Gisèle Freund, who remained a faithful friend and whose portraits he admired, realizing that “everything is seen on a face.” His figurative and representational paintings were still influenced by the School of Paris, in particular Soutine. He painted with oils and seriously applied himself to engraving.

In 1970, his first daughter was born. He then divided his time between Paris and Collias, a village in the Gard where the baker was none other than his cousin, Ernest Frankel, a former resistance fighter and survivor of Dachau and Buchenwald. There, Rozen spent years renovating a small house where he would work every summer, enjoying, like Chagall, Cézanne or his contemporary Anselm Kiefer, the light radiating from the garrigue and filling their studios. He made a definitive break with realism. In 1972 and 1973, he created and directed the Collias Festival, inviting famous musicians, painters and filmmakers. Jean-Louis Trintignant, a neighbor, lent them his courtyard for a theatrical creation.

In 1974, Felix Rozen became a French citizen; and exhibited at the Simone Badinier Gallery canvases that were “bursting with brilliance, [expressing] a wild commitment of spirit and heart,” the poet Pierre Béarn wrote.

That same Spring, he met art critic Georgina Oliver, who became his second wife and with whom he had four children.

Over the decades, he branched out into a multiplicity of artistic fields, becoming a sculptor, author and actor of performances, poster artist for French public radio France Culture and director of short films. He also taught at the École des Beaux-Arts in Besançon, the University of Vincennes and the Sorbonne.

From 1977 onward Felix Rozen lived and worked in Boulogne-Billancourt where he obtained, thanks to the support of the painter Georges Mathieu, a work space near Île Seguin.

Felix Rozen next sought to elaborate a compositional language of his own. He who had always dreamed of becoming a conductor compiled notebooks bearing witness to abundant research around symbols and abstract signs, mixing music and painting. His works evolved, suggesting archaeological strata. The poet and essayist, Jacques Lacarrière, a promirent Hellenist, spoke of “palimpsests”.

At this moment, he got closer to Christian Dotremont and Pierre Alechinsky, members of the COBRA movement, and began a series of photographic portraits of artists.

In 1977, he participated in group exhibitions with Bram Van Velde, Aristide Caillaud, Jean Messagier.

In 1979-1980, he spent several months in New York. At the Chelsea Hotel, he worked on lines and zigzags, wax and pigments (New York Series).

Back in France, music was now at the heart of his experiments in the visual arts. In January 1981, he created for Jean-Yves Bosseur and the Intervalles ensemble the graphic score Uncertain Opus. This would open the doors of the Center for Music Experiment in San Diego and New York University, where his computer-generated Computer Series combined sounds, images and computer science.

In 1985, Felix Rozen went to Tokyo. He worked on Japanese paper, to which he attributed a key quality: that it allows “colors to vibrate.” His Tokyo Series attests to this.

In 1990, he developed a wax and fire engraving process called Pyrocera, which he patented at France’s National Institute of Industrial Property. He extended this process to painting, which enabled him in his series Mysteries and Double Vision, both a type of low-relief-sculpture, as he himself called them, to create a third pictorial dimension, evoking time.In 2004, a retrospective was organized at the Musée des Années 30 in Boulogne-Billancourt. In December 2005, the Jeanne Bucher Gallery dedicated an exhibition to him focusing on his Letters to Paul Klee.

The Plagales Sequences, London Calling, Venice Calling and Digital Traces followed: collecting from his printer scraps of offset reproductions from his catalogs, he transformed them, covering them with layers of paint that he scratched, clawed or caressed with specially-conceived one-of-a-kind tools producing small-format works.

In 2010, though suffering from a neurodegenerative disease, he did not drop his paintbrushes. His sense of perception was modified, blurred… leading to the emergence of a Série floue/Blurry Series, which has never been exhibited. He died on October 6, 2013. His loved ones created an association to share his work with the general public.